Overview

By the late 1950’s the Porsche 356, still very much VW Beetle-based, was becoming less and less competitive. The Porsche brand needed a new car, and a team led by Ferdinand’s son, Ferry, started work on it.

A wishlist written down by Ferry Porsche on squared notepaper included the following features: “2-seater with 2 comfortable jump seats. Rear view mirror integrated in the fenders. Easier entry”. At the same time, the Sales Department demanded the following: “Retain previous Porsche line. Not a fundamentally new car. Sporty character”. The development direction was therefore clear: evolution, not revolution (it remains the same today!). The same also applied to the technology. The drive principle – including a flat, air-cooled “boxer” engine at the rear – would remain intact, but the chassis would be modestly re-engineered.

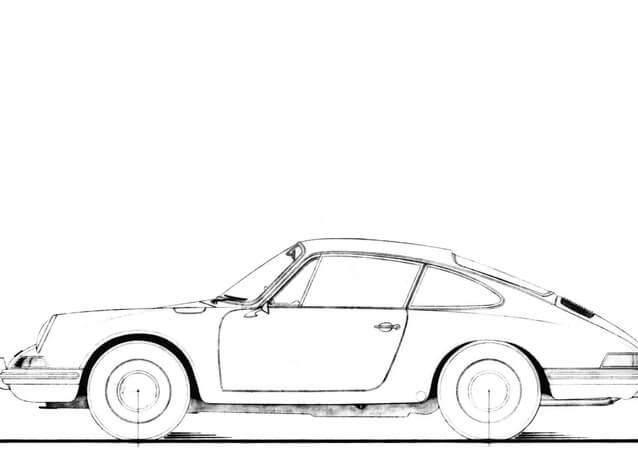

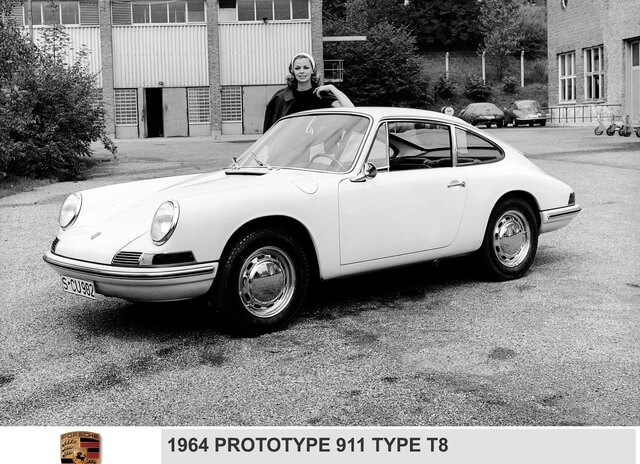

A number of prototypes were built, including the true 4-seater prototype 754T7, penned largely by Ferry’s son, Ferdinand Alexander Porsche. The board decided, however, to shorten the wheelbase and to change the shape of the rear of the body, doing away with the distinctive notchback, and creating the iconic 911 flowing form as we know it. Descendants of Erwin Komenda, namely his daughter, have claimed in a lawsuit directed at VW Group, that he was, in fact, the true author of the 911 body, and that he had never been fully compensated for his groundbreaking work.

The benchmark for the new Porsche would be the 356 with the so-called “Dame” motor of 1.6 liter capacity, the benchmark in terms of smoothness and vibrations. As the 4-cylinder Fuhrmann unit had reached the limit of its development, a new 2-liter 6-cylinder engine was developed.

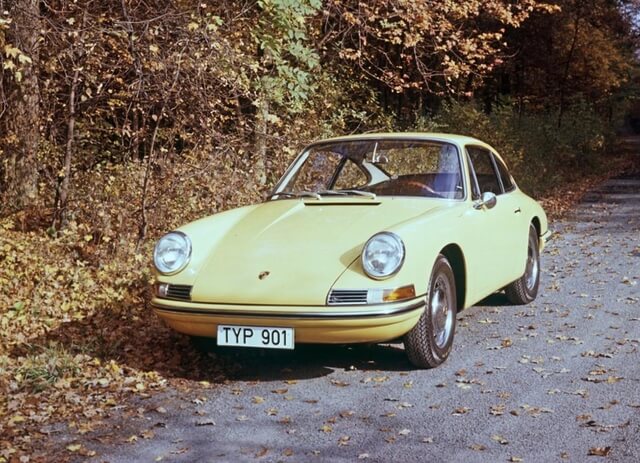

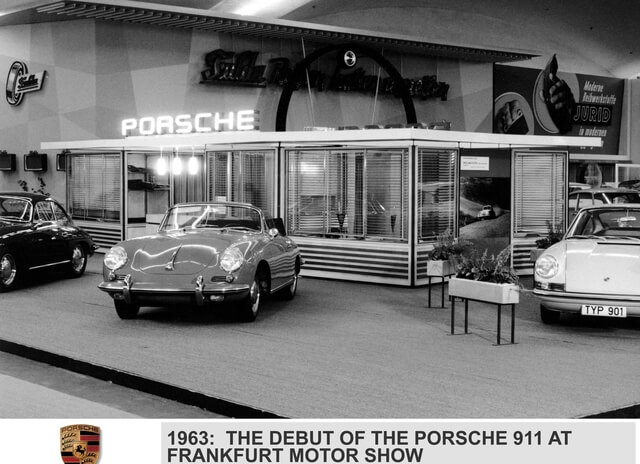

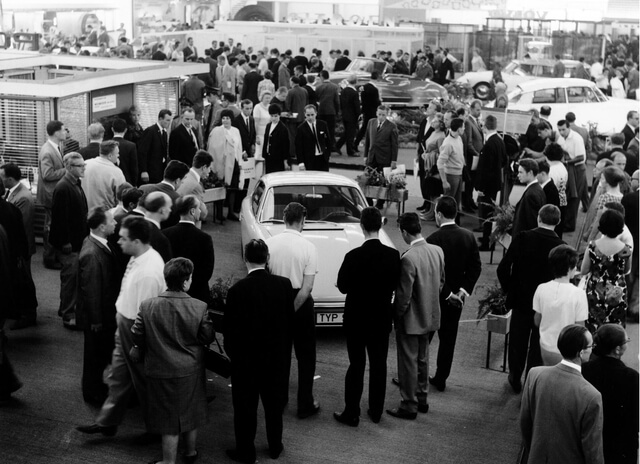

The Porsche 901 in prototype form was shown at the Frankfurt Motor Show in 1963, but when it was displayed in Paris the following year, Peugeot vetoed the model designation: it had filed for trademark protection on all numeric car model names with a “0” in the middle. After 82 units had been produced (rare and much coveted now), the model designation was changed to the familiar “911”.

The car was criticized in period for its wayward handling, and to some extent this was justified. Very rudimentary suspension solutions plus period tires made the car very oversteery. Today’s tires tame the handling somewhat, and most owners tend to drive their cars very gently anyway. In truth, I believe the early 911 is not very pleasant to drive for the modern driver, as it’s quite physical and requires attention at all times. Once a slide begins, it’s difficult to catch due to the slow, unassisted steering. Most owners buy these cars out of nostalgia or due to their rising values, not as a means of delivering great driving pleasure.

This DRIVERSHALL Buying Guide covers all early 911s except the Targa and the 912, which will be covered by a separate installment.

Engine

At the start, the 901 was equipped with a 2-liter engine developing 130 hp. In 1965 a version of the engine appeared, replacing the maintenance-intensive Solex carburetors with Webers. In 1968 the 911 S appeared with 160 hp, the 911 T with 110 hp became the entry model, and the base car was now called the 911 L. The engine block and the gearbox casing were then made of a magnesium alloy.

In 1969, when Bosch intake track injection was introduced, the engines gained an extra 10 hp: the 911 E was the base model, and the S was the most powerful one, with the T retaining carburetors until the end of its production.

In 1972 the engine capacity grew to 2.2 liters, and later to 2.4 liters, with the final 911 S developing 190 hp. The most powerful factory engine was the 1973 Carrera RS with light alloy cylinders and 210 hp.

The main source of problems with the early 911 engines is the wear and failure of camshaft drive chains and chain tensioners. Cars with low mileage and irregular servicing are especially prone. Another problem area are the engine head bolts securing the cylinders to the engine block: these can fail catastrophically due to age-related corrosion, and this failure can have nothing to do with the mileage.

It is very expensive to replace a corroded exhaust heat exchanger: this has to be checked by a specialist in early 911s. As the Solex carbs used initially required frequent adjustment, these were often replaced in period with Webers or Zeniths, but original carburetors have a higher collector value. Magnesium engine blocks and gearboxes tend to leak oil. Cars sourced from the US often have the K-Jetronic Bosch fuel injection and are more expensive to fix.

Gearbox

Most early Porsche 911s are equipped with a 4-speed manual gearbox. Much fewer have a 5-speed or the Sportomatic semiautomatic transmission (the latter offered from 1967). The standard gearbox is noisy and requires a firm hand, but is quite durable. As of 1971 the gearbox was replaced with a 915-series unit, with a better shifting action.

Bodywork

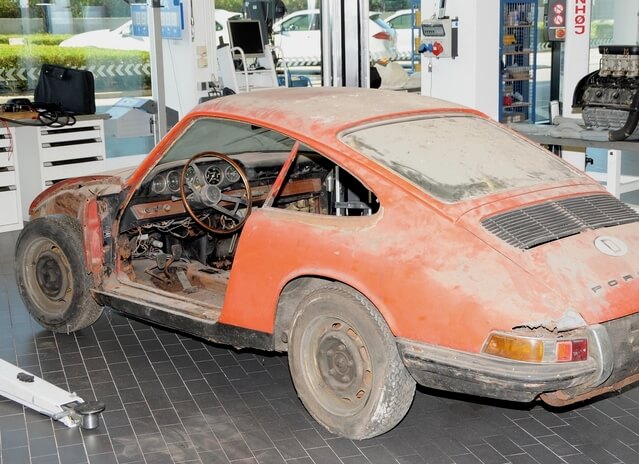

At the beginning Porsche cars were not as well made as they are now, or have been since the 1980’s. Older early 911s rust practically everywhere, and most have been repaired, the question therefore is: how well?

Most of these cars rust prodigiously around the headlights, front wheelarches and all the way to the base of the B-pillar. Suspension mounting points also corrode, as do the lower parts of the A-pillars. Another critical area is the special tube to which the rear suspension is attached.

Look for deformations in the inner body structure which can indicate hidden accident repairs! Leaking rubber seals of the rear and side windows mean water ingress into the hat shelf area, which in turn causes corrosionin the rearmost parts of the chassis longerons and the engine bay.

If a car you wish to buy seems to have been restored/repaired/welded, you unconditionally need the help of a seasoned specialist. In the case of cars imported from the USA, often claimed to come from so-called “dry states”, the body repairs performed there are often of horrible quality, just cleverly disguised.

Chassis

The suspension of the early 911 was composed of longitudinal torsion bars and wishbones in the front, and torsion bars plus semi-trailing arms in the rear. The rear arms were lengthened in 1971, resulting in a lengthening of the car’s wheelbase. The car had four disc brakes, later ventilated. At the beginning it has a single-circuit braking system, replaced by a double-ccircuit system in 1968.

It is crucial that the whole suspension system be in perfect shape, correctly maintained and adjusted, with parts replaced on time. The car is quite difficult to drive as it is, and with worn-out suspension it can become impossible to handle for an inexperienced driver. Low mileage is no guarantee of chassis condition.

Interior

The interior needs to be as authentic as possible with no visible damage. Depending on where the car spent most of its life, look for water ingress traces and plastic trim cracked from excessive exposure to sunlight. Replacement parts are available, mostly from Porsche Classic, but are very expensive. Buy the best car you can find.

The Story

1963: Porsche 901 shown at the Frankfurt Motor Show

1964: launch in Paris, name changed to 911

1967: 911T introduced, Sportomatic gearbox available

1968: double-circuit brakes introduced

1969: engine enlarged to 2.2 liters

1971: engine enlarged to 2.4 liters, new Typ 915 gearbox introduced

1972: RS 2.7 launched, 1308 Touring versions built, 217 units of Sport, 10 prototypes and 55 of the RSR

1973: production stopped, 81 100 units built in total

Specifications

Porsche 901

Power 130 hp

Top speed 205 km/h

0-100 km/h 9.1 s

The DRIVERSHALL Verdict

If a car seems to good to be true, it is. The early 911s which have become very sought after are beloved by dark characters of the classic car world. A cosmetically beautiful car can hide a rotten body. Unless the car is perfectly documented and sourced from a known vendor, try to look for a vehicle which is a bit ugly, displaying an original patina on the body and inside the cockpit, as it is easier to detect traces of bad repairs and fake restoration work. A 911 with well-disguised corrosion and component wear will be a veritable money pit.