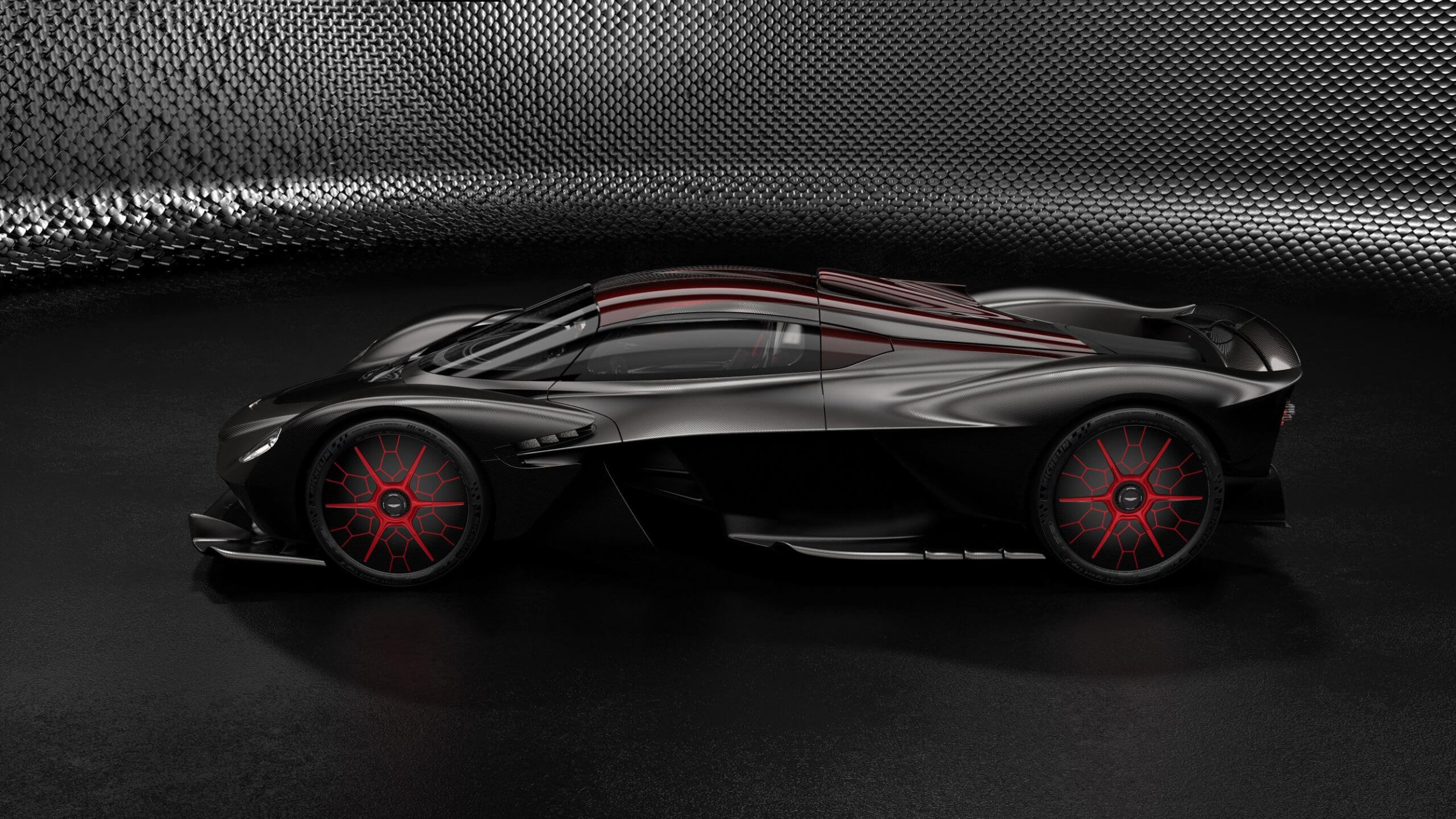

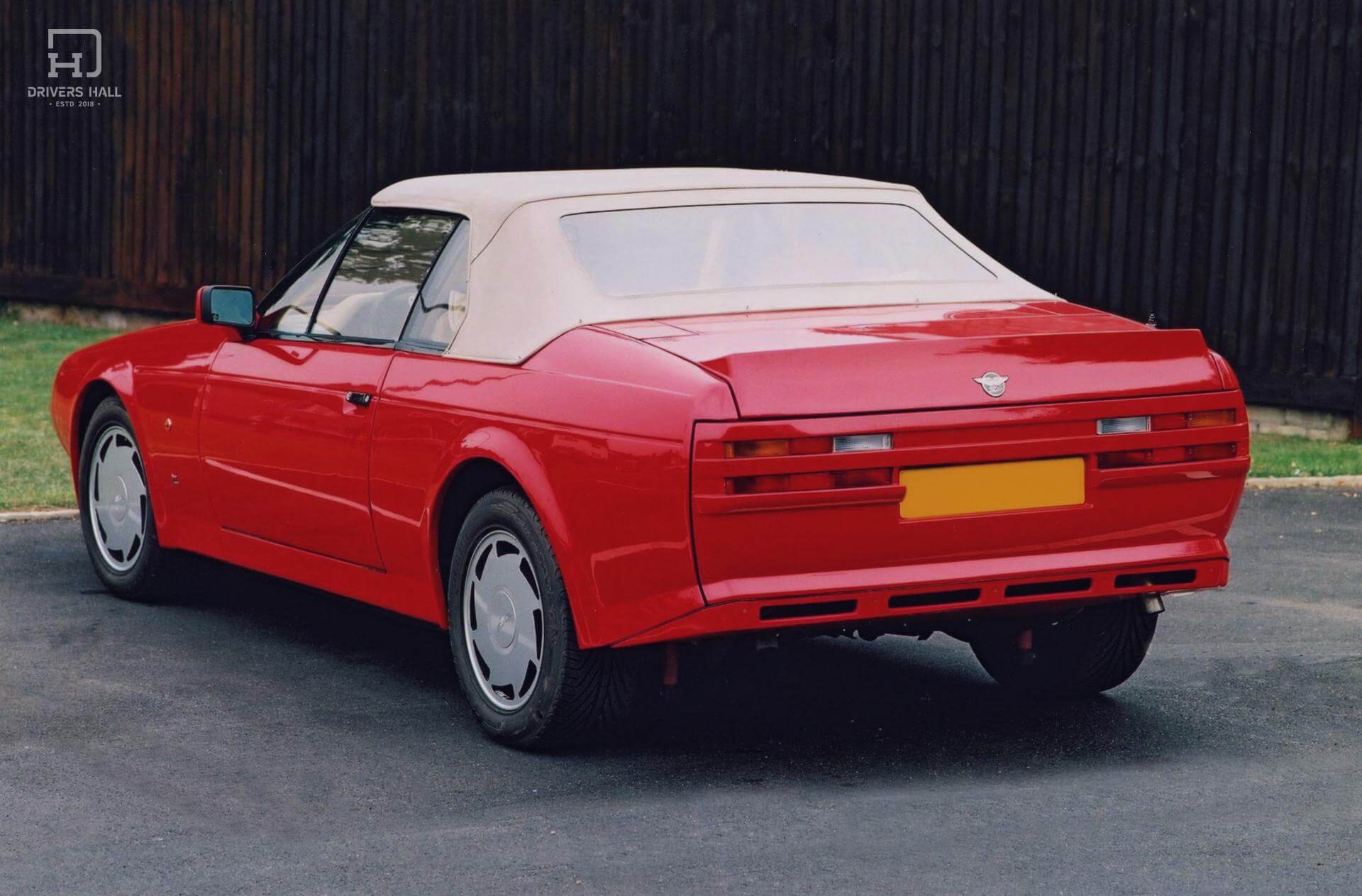

Some people like to make noise, be visible, create waves. Others prefer to blend into the background, do whatever needs to be done, move without attracting attention. Well, it’s not really easy not to attract attention while driving a two-tone Rolls-Royce, but simultaneously this car is the opposite of all those gaudy, noisy supercars which are the equivalent of a bunch of peacock feathers stuck into a Victorian hat. It can do things none of them can, too.

Contemplating a long-distance trip? Thinking of using your Rolls instead of suffering the hustle and bustle of airports, and the envious stares of foreign officials when boarding a private jet? Why not, indeed. Two people can travel aboard it in cosseting luxury, and four in astonishing comfort. This example, like any modern Rolls-Royce, is entirely bespoke, built to a unique order. With a total price, excluding taxes, of £284,025, it not only sports the two-tone finish of Black and Arctic White, but also an interior trimmed in fabulously supple Purple Silk leather. Extras? Yes, there are some, including 21-inch part-polished ten spoke wheels, a camera system and a Bespoke Rolls-Royce Audio system. The two latter ones are worth their weight in gold, especially the audio. The camera system helps when pulling ouf of blind junctions, where instead of guesswork and of suddenly blocking someone’s way with the bulk of the Rolls’ bodywork, you can look at a a screen (which can also display a NightVision image when driving in poor visibility) and see all the oncoming traffic. The sound system… Well, it is the best I have experienced in a motor vehicle. The clarity and faithfulness of the sound image are stunning, and nowhere do my opera and jazz CD’s sound so lifelike. It is a true audiophile-grade system, with no useless controls to distract the listener, and the purest sound of a cello outside of Yo-Yo Ma’s living room.

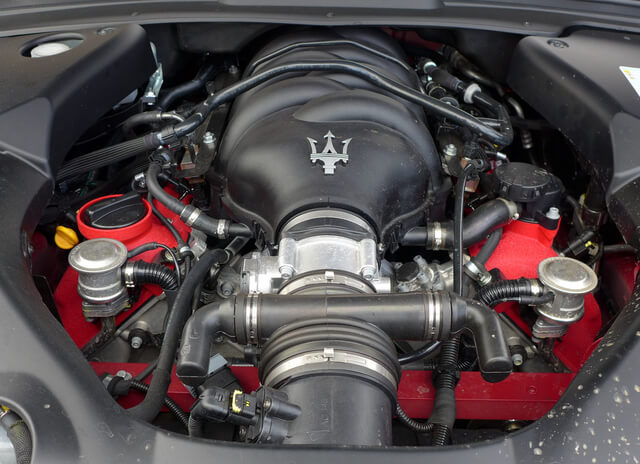

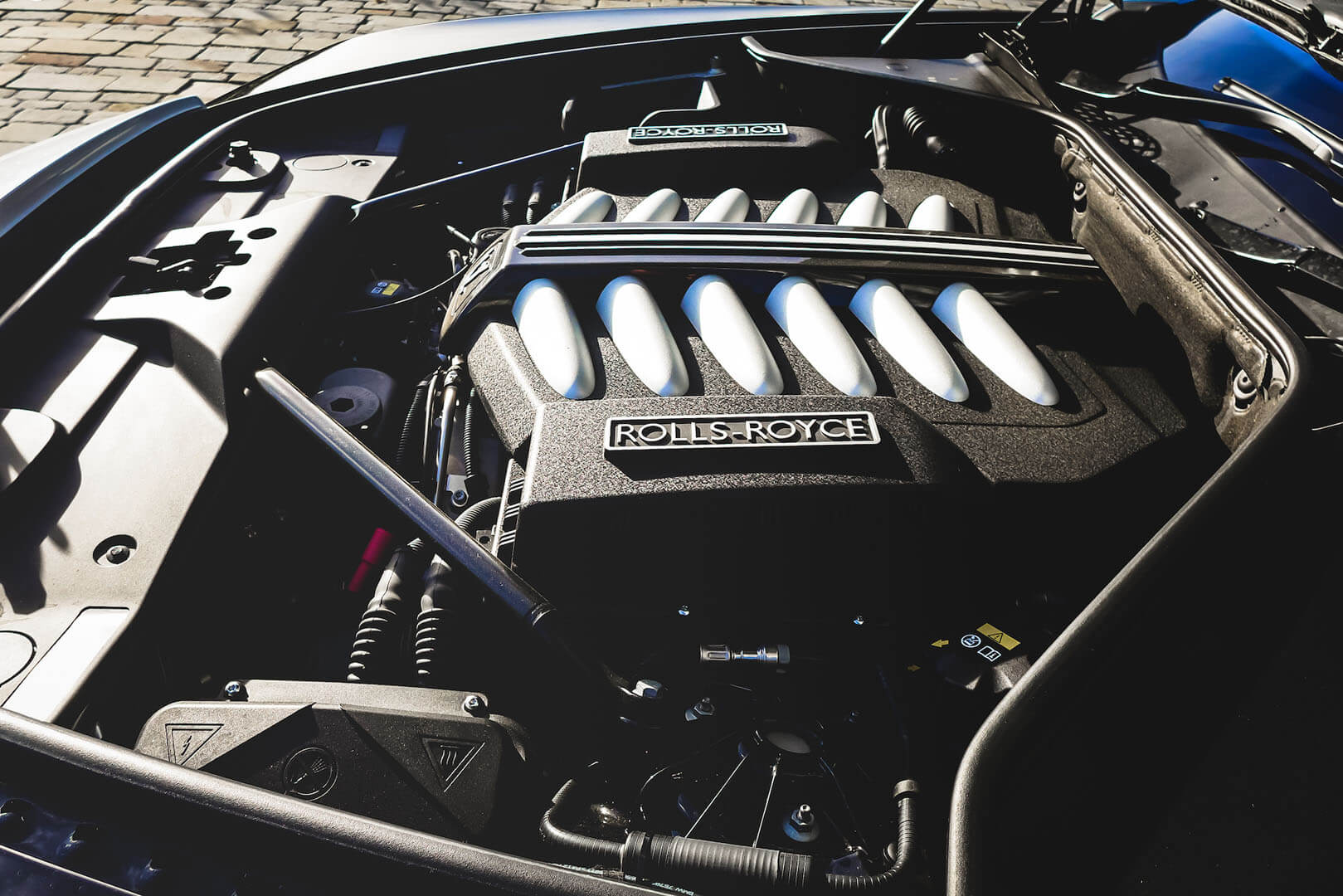

And it is no slouch, either. The new breed of supercar drivers, those who abhor corners and thrive on traffic light grands prix, perhaps would not be satisfied, but who cares. The very large Wraith is capable of the 0-100 km/h sprint in 4.6 seconds, and can keep accelerating, effortlessly, all the way until its artificially governed 250 km/h top speed. It is much more aerodynamic than it seems on a superficial level, but nevertheless aerodynamics mean little hen faced with a turbocharged V-12 engine, developing 632 horsepower and 820 Nm of torque, driving the rear wheels of the 2360 kg machine via a silky-smooth 8-speed automatic gearbox. The transmission is helped by data from the satellite navigation system, and is able to predict corners and instances when it is necessary to hold on to a given gear. And it really works. The only thing it can’t recognize is gradients, and the data is included in the stream from a GPS receiver, so I still hope Rolls-Royce engineers will find a way to integrate it in the future. In terms of performance it’s a true GT, capable of staying with the fastest cars on Earth on a lengthy trip across the continent. The people aboard the Wraith will arrive unruffled. In contrast, supercar passengers will end their journey exhausted, deafened, shaken and stirred, the opposite of traditional grand touring. The Starlight Headliner, with its 1,600 LEDs sewn by hand into the fabric, provides an added touch of true luxury: dimmed down, it provides a subtle ambient light which the eyes never tire of.

Does it go round corners? You bet it does. Not in the way of a 911, and with noticeably more body roll, but body roll is good: it tells you what the car is doing. The steering is light, but precise and linear, and gives the driver enough confidence to press on. If you don’t forget the considerable weight, the braking will also be sufficient: in reality it weighs the same as a fully equipped Porsche Cayenne! Don’t act rashly, and the Wraith will help you go very fast indeed. The only thing I don’t like is the lane-keeping assistance which, on crowned and strangely cambered roads, imparts the sensation of vagueness in the steering around the straight-ahead position. Once the assistance is switched off (for instances by picking the Traction mode of the DSC stability control), the sensation disappears. It is a minor point anyway.

In order to test the Rolls-Royce Wraith’s ability to cover long distances with ease, I decided to travel to a location where it could meet one if its spiritual ancestors, the Merlin aviation engine. It not only powered the legendary Supermarine Spitfire fighter plane, but also the sleek P-51 Mustang, the Avro Lancaster bomber and many other Allied aircraft. Aviation piston engines have always been more advanced than car engines in terms of their power-to-weight ratio, and the technical solutions used to produce power. Aircraft engines therefore used supercharging and exhaust gas turbocharging very widely, in order to improve the performance at high altitudes, much earlier than car engines started to utilize those means of forced induction.

The Merlin is also a V-12 layout, like the engine of the Wraith, and it is turbocharged. The fuel supply to the cylinders is handled by carburetors in the Merlin, of course, and not a sophisticated fuel injection system with electronic engine management like in the Wraith, but a similarity, at least in spirit, exists. There is a considerable difference between them in terms of engine capacity, however, as the swept volume of a Merlin is around 27 liters, and the current Rolls engine is only 6.6 liters. The two companies are now totally unrelated, and only share a name, but back in time there was only one Rolls-Royce, and the name always stood for unparalleled excellence. Today, driving the Wraith to the Shuttleworth Collection at Old Warden Aerodrome (www.shuttleworth.org) I could not help thinking that there was indeed such a thing as beautiful technology. Things which simply look right, and work well. Shuttleworth maintains one of the oldest fleets of fantastic historic aircraft in the world, and works very hard to preserve them (and a lot of cars!) for posterity. The Wraith, standing side by side with their 1941 Spitfire Mk.VC in the livery of the 310 Czech Squadron, reminds me of all the attributes of modernity we take for granted. Including peace and freedom.

Many thanks to the wonderful people at the Shuttleworth Collection for their help with the production of this feature.