Overview

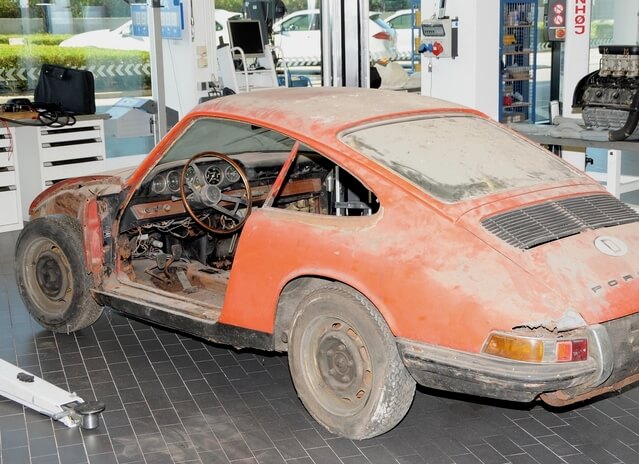

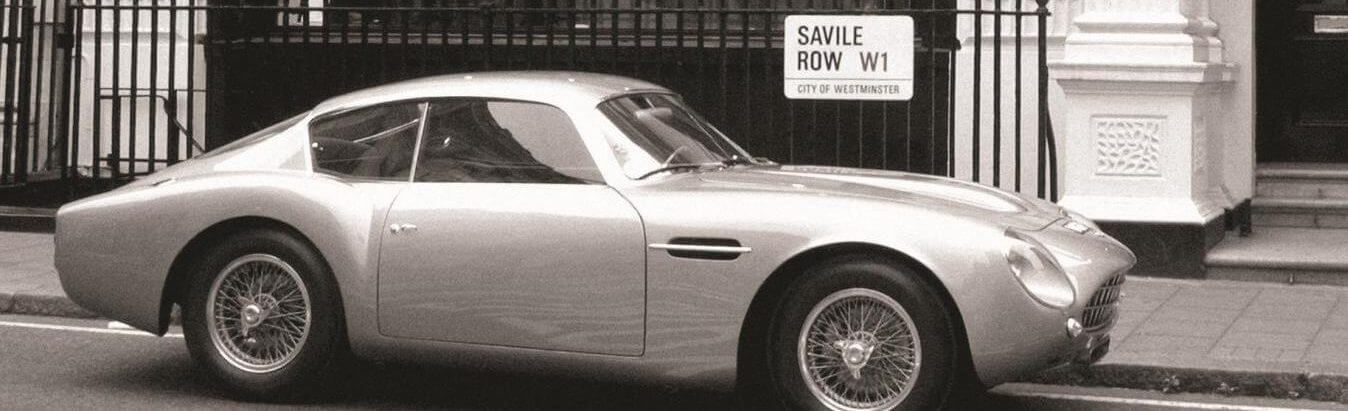

The Jaguar E-type is probably the most desirable classic car, period. Everybody knows what it looks like, and most people want one. Even Enzo Ferrari has been quoted as saying that it was the most beautiful car in the world. Its notoriety also means that it is now impossible to expect an honest bargain, and utmost care should be taken to avoid unscrupulous vendors. American “barn find” cars are not necessarily in good condition, and botched, unprofessional restorations mean that they will bite their naive owners after a few years, painfully. Paradoxically, it is very easy to own or upgrade a Jaguar E-type nowadays, as parts are widely available, but very difficult to purchase a good one. You must buy one from a trusted specialist, or seek the advice of one when buying privately. Otherwise it could turn into an expensive disaster.

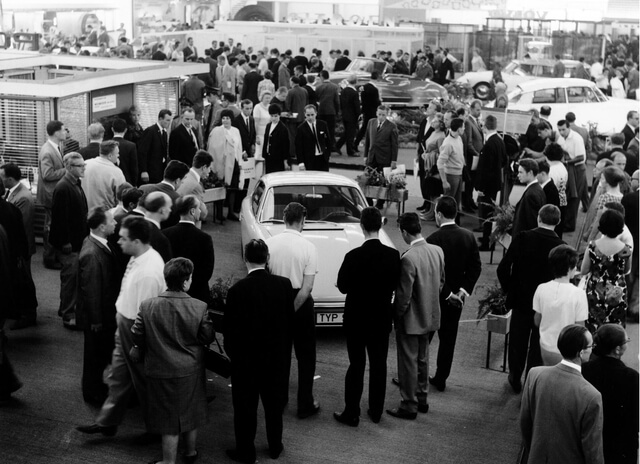

Its launch in 1961 is the stuff of legend, with the Geneva show car being driven non-stop from England so that it would get to the Jaguar stand on time. At the beginning, demand outstripped supply, and William Lyons, the boss of Jaguar, was very happy. The original Series 1 cars were followed by modified Series 2 and Series 3 cars, and the car stayed in production until 1975, when it was replaced by the XJ-S, also designed by Malcolm Sayer. The later, bulkier Series 3 cars are less liked, but good to drive. Unless you plan on just waiting for values to rise, and you wish to use your E-type as its makers intended, please look for the best car you can afford, regardless of the series. Upgrades are quite popular, except on the most valuable cars in concours condition; these modifications include uprated brakes, uprated engines, 5-speed gearboxes, fuel injection etc.

Jaguar only homologated the Series 1 to race, therefore with today’s proliferation of E-types in historic racing, this has distorted the market, making S1 cars even more valuable. Roadsters used to be more pricey, but the coupe values have recently caught up. The widespread obsession with matching numbers means that some numbers may have been restamped on some cars by unscrupulous traders! Beware of that. Note that competition cars, which in period were treated as mere tools, cannot have matching numbers: engines were replaced as needed and nobody cared. If a car has a genuine racing history, it can’t have matching numbers and vice versa.

Engine

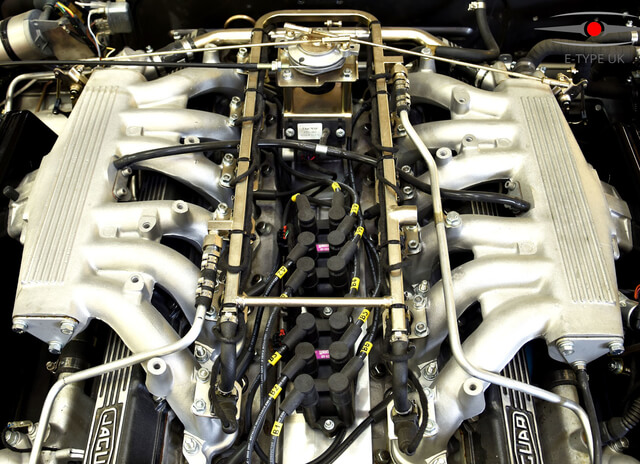

Most available E-types are powered by Jaguar’s long-lived 6-cylinder inline engine, with a capacity of either 3.8 and 4.2 liters, and some with the V-12. The sixes are basically tough, if they are properly maintained and rebuilt every 150,000 miles or sooner. Check the underside of the oil filler cap; if it’s covered in a whitish sludge, it means that the head gasket has blown due to the engine having overheated (the reasons for overheating may be multiple, blocked water passages, lack of maintenance, faulty cooling fan, coolant leaks).

If the vendor has warmed up the engine before you view the car, be suspicious because a cold start can help you detect rattles and knocks. Let the engine run and see if the fan operates as it should once the engine is hot. Should the engine rattle when cold and produce smoke, it needs to be rebuilt. All parts and complete engines are available, and it is now possible to build a motor which is much better than what Jaguar put under the hood when the car was new! Ports and combustion chambers in new heads really align with the cylinders, making new-build engines more powerful and more reliable; but, of course, in terms of value, originality counts. Rough running is often down to carburetors needing an overhaul.

The V-12 engine in the S3 is very strong, lasting up to 200,000 miles between overhauls, but only with careful maintenance. It needs to be gently warmed up before driving, so that oil can lubricate all the critical parts. If the correct proportions of antifreeze are not maintained, the engine can expire. You may find that previous owners skimped on maintenance, using plain water as coolant, and never touching the spark plugs at the back of the engine (or the rear inboard brakes…).

The rubber coolant hoses, of which there are many in both types of engine, must be replaced periodically, and not when they have already perished. The same applies to the flexible fuel lines. Some of them are hard to reach, but if you bow to laziness, a ruptured fuel line may lead to your investment going up in flames, literally.

There is nothing that cannot be repaired or improved on any of the E-type engines.

Gearbox

Transmissions are strong, but the legendary Moss unit is known for its unpleasant shifting quality and for its level of noise. A rebuild can be expensive, however. The differential is quite expensive to overhaul, as special tools are required to do the job. There are several final drive ratios available, make sure your car has the correct one (American axle ratios are different).

The automatic 3-speed Borg-Warner box causes no serious problems, and when it begins slipping, a rebuild is not expensive and fairly straightforward. In fact all the transmissions fitted to the E-type in production are easy to repair and all parts are available.

Suspension and brakes

The suspension is one of the best-designed bits of the car! The most crucial part (others need replacement and lubrication, but this one can kill you when it breaks) is a little coupling which connects to the upper wishbone/driveshaft. Almost nobody ever checks it or replaces it on time, and it will not warn the driver of the impending doom. When it fails, the wheel folds under the car with catastrophic consequences. At CKL Developments at least 10 instances of serious crashes are known, therefore a modified part is installed, made of high-tensile steel.

When you buy a car like this, you never know when a particular component has been replaced, perhaps it is overtightened and subject to metal fatigue. Therefore this little component, and the driveshafts, should be replaced like parts on an aircraft, after a certain number of hours in use. You can’t see this part, and you don’t know it’s worn until it fails completely!

The steering should feel taut and precise, if it isn’t, the two joints in the steering column may be the culprits (available at reasonable prices) or, alternatively, worn suspension bushes. Check all joints, splines, and couplings for the sake of safety.

The handbrake mechanism has a tendency to seize, but is not difficult to loosen up and lubricate properly. Differential oil may leak on the rear inboard disc brakes, which may cause trouble.

Bodywork

An E-type will happily rust all over. A European or US car must have had some considerable repair work done at some point, and it is important to know whether the work has been done well, and if the right welding process was used, plus the correct original repair techniques. No car can now be completely original, so if someone claims that his is, that is a lie. California-sourced cars may be in better condition, but not always. The front tubular subframe may be damaged by jacking the car up the wrong way, and the tubes can have fatigue cracks around the engine mounting points.

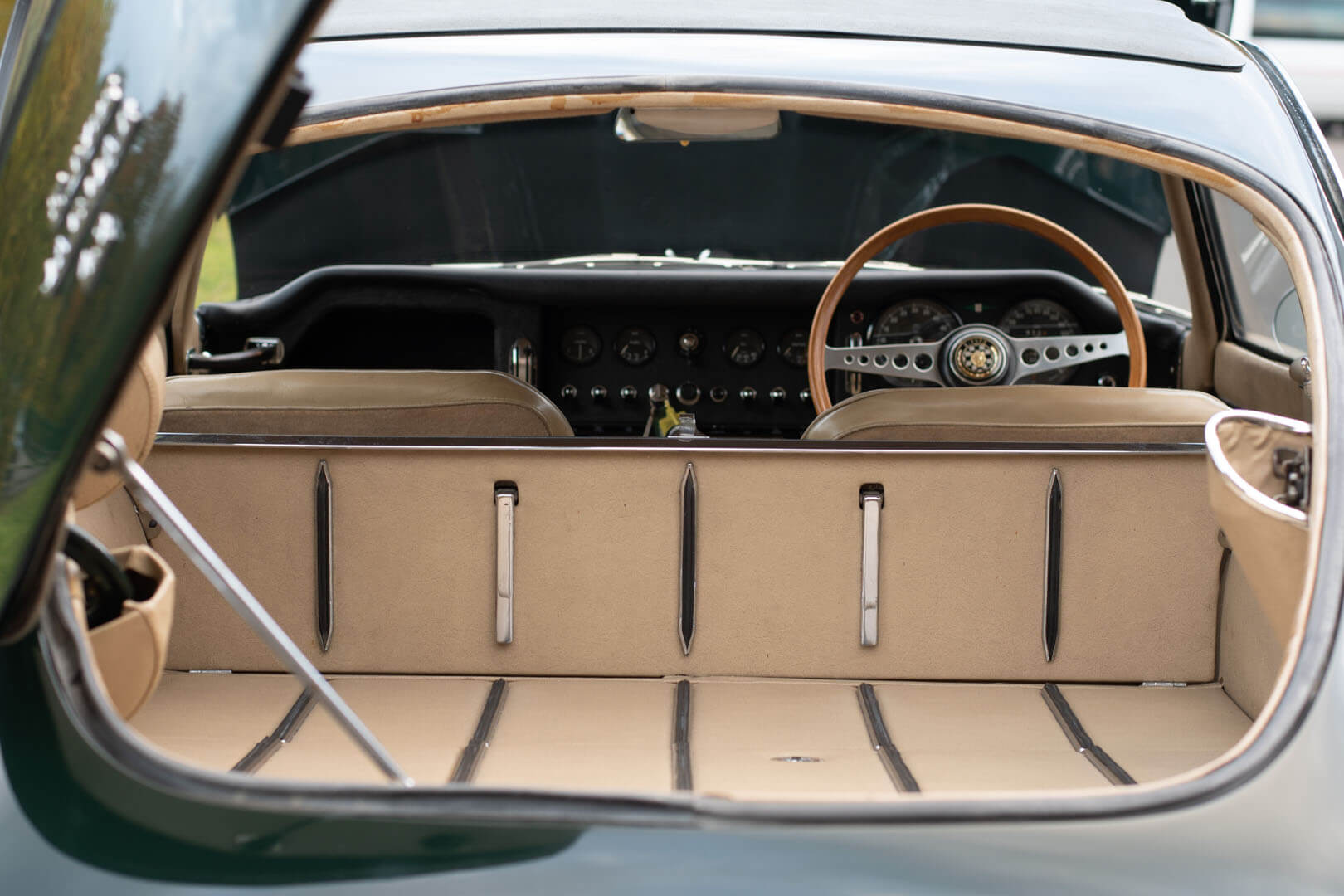

Interior

At this age, interior trim may be worn and/or damaged. Most parts are available, although the quality of some of them leaves a lot to be desired. For high-value cars, there is no substitute for originality, and if you try hard, you can usually find parts somewhere.

The Story

1961: Jaguar E-type launched at the Geneva motor show

1962: Deeper footwells in the floor in front; that is why earlier units are known as flat-floor cars

1964: Engine grows to 4.2 liters, new gearbox fitted

1966: 2+2 E-type available, longer wheelbase and higher roof

1967: Series 1 1/2 model in production, with headlight fairings gone

1968: Series 2 on sale

1971: V12 Series 3 replaces the inline-6-engined S2

1975: production ends

The DRIVERSHALL Verdict

There are no bargains among E-types. Buy the best car you can find, with a fully documented history, and have it checked by a specialist. Otherwise find a project car whose condition is obvious, and budget for a full restoration. Values are high, and you need to be careful in order to invest well.

Many thanks to Rupert Manwaring and Chris Keith-Lucas at CKL Developments (ckl.co.uk) for their help with this feature.