Most people today connect the iconic BMW 507 with Elvis Presley, who owned one, recently restored to its former glory, and with some unspecified golden age in the history of the Munich-based brand. In fact that beautiful car was a commercial disaster, wasn’t too good to drive and that period in the history of BMW was one burdened by doom and gloom…

During WWII BMW did not really build cars, as in those days a ministry told the industrialists what it wanted them to manufacture, sometimes making for very strange bedfellows (Mercedes built Opel Blitz trucks for a while). With its aviation engine production capacity growing (it acquired the Bramo company) it was told to develop and produce as many airplane motors as it could. While developing the arguably best radial engine of World War II, the BMW 801 of Focke-Wulf Fw-190 fame, it also worked on jet engines and managed to start the production of one, the 003, before hostilities ended. That engine did not contribute anything of importance to The Reich’s war effort, but captured engines taught the war winners a lot, especially the Soviets. BMW also produced its excellent motorbikes for military use, and that was that.

My personal favorite BMW product from the war era is the incredible BMW 803 piston engine, intended for heavy bomber aircraft, including the so-called Amerikabomber. It had four rows of seven cylinders each, 28 in total, driving twin counter-rotating propellers through a special gearbox. The engine’s capacity was a scarcely believable 83.5 liters, it had sodium-filled exhaust valves, direct fuel injection and supercharging, and developed almost 4000 hp with a dry weight of around 3 tons. In 1944. It never found practical use, and at that time jet and turboprop engines were already considered more future-proof. The only surviving example is on display at the Deutsche Flugwerft in Schleissheim near Munich, a branch of the Deutsches Museum (next to many other totally unique things to see), and is a monster of complex technology and lateral thinking, so typical of the German aviation industry in the 1940’s. Too complicated to succeed under war conditions, but beautiful as a concept.

Right after the war BMW almost ceased to exist. Its main carbuilding facility in Eisenach found itself under Soviet occupation, and the Soviets told their tame East Germans who had officially all been anti-Fascists (a statistical impossibility) to restart production. This they did, and, using the undamaged tooling and the stock of parts, began to turn out brand new cars like the 327. BMW was too weak for its protest to be heard, but after a while the Soviet masters told their GDR puppets to change the name to “EMW” so as not to cause further conflict with the West. In East Germany this was common practice, as factories were taken over, Horch vehicles were produced until the parts lasted, the Wartburg two-stroke car was created using 1930’s DKW technology, and the Robur truck was a mildly restyled Phänomen. Because the American occupying forces did not permit BMW to restart vehicle production, it resorted to making pots and pans, and thus contributed to the rebuilding of Germany and its subsequent economic miracle. The Munich facility, which used to make aircraft engines, was reduced to rubble and very little could be salvaged. Nevertheless the BMW management persevered, and kept begging the Americans for permission. In the changing political climate this was granted, and in 1948 the production of the R24 motorcycle commenced. BMW was back in the game.

It was alive, but only just, and had no car to build. One of the managers tried talking to Ford and Simca to produce their vehicles under license, which would pay for factory tooling, but the talks got nowhere. Germany was poor and BMW’s chief engineer, Alfred Böning, believed a cheap car was the answer: the motorcycle engine-powered 331 looked like a scaled-down prewar BMW model, but the board did not approve it for production. It was vetoed by the former banker and Opel plant manager, Herr Grewenig, who believed, correctly, that for a while BMW would not possess a large enough factory to efficiently produce a cheap car while making money on it, and he pushed for the creation of luxury automobiles which could be made in small numbers and with a more sizeable profit margin. He won in the end, and he had Böning design the BMW 501.

This car, powered by a 6-cylinder engine, a development of a design before the war, was delayed, too heavy, underpowered, and cost as much as an average German earned in four years, not exactly a recipe for commercial success. The bodies were built at subcontractor Baur in Stuttgart, because of delays to in-house facilities, thus adding to the cost. The 501 was updated after a while, and in 1954 a parallel model was introduced, the 502, with a new, 2.6 liter V8 engine, designed by Bőning and Fiedler (the same Fiedler who was instrumental in the creation of the 328 before the war, and who earlier had gone away to work for Bristol Cars in England). Sales of the 501 and 502 were finally healthy, but insufficient for the company to develop. The next stage of BMW’s history involves Max Hoffman, the same former Austrian Rolls-Royce and Bentley dealer who sold cars on the East Coast of the United States, so important in the history of Mercedes and Porsche. In those days influential car importers could actually have a say in what car makers built, especially people like Max Hoffman and Luigi Chinetti, people with a strong track record in sales. People who made trends, not waited for them.

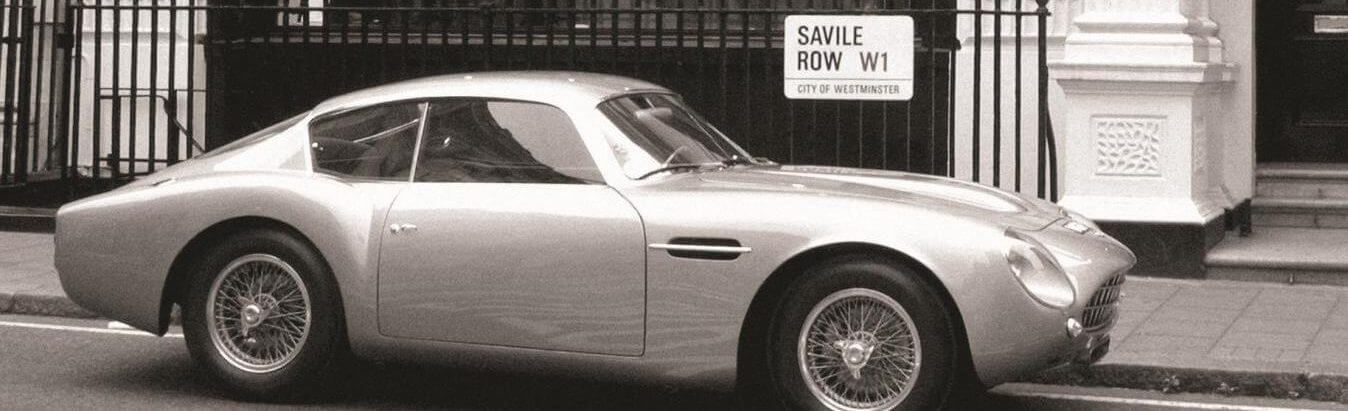

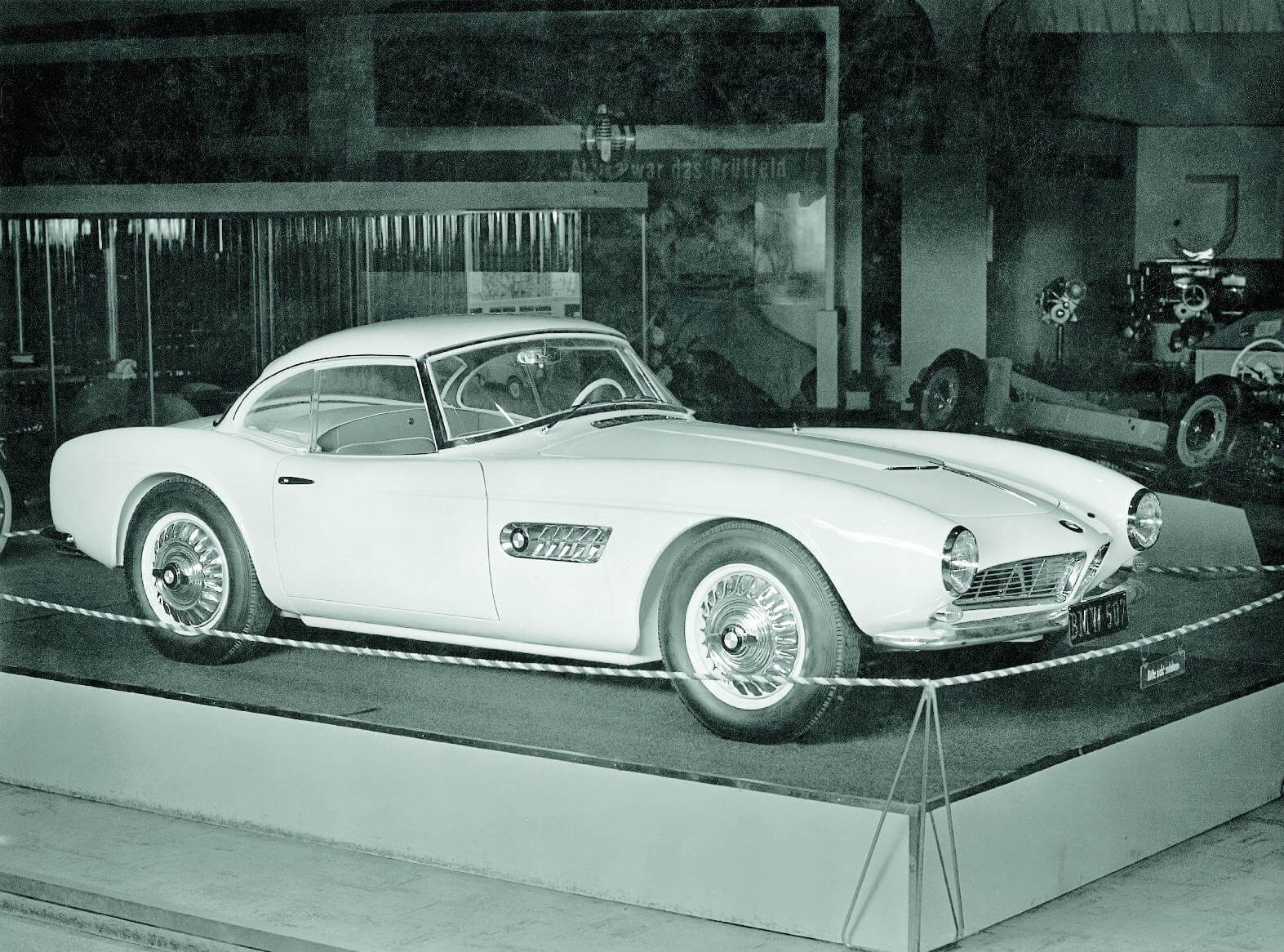

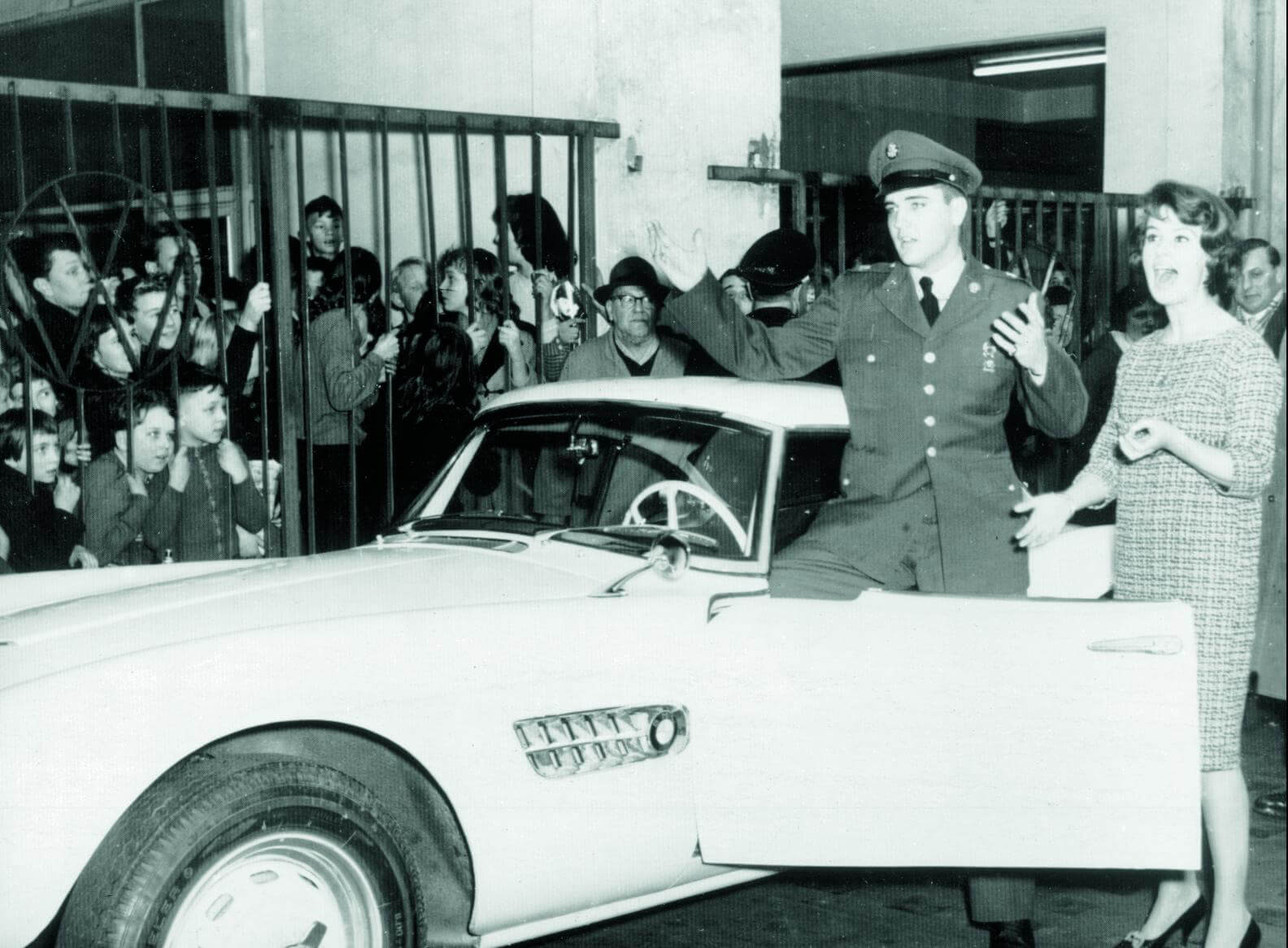

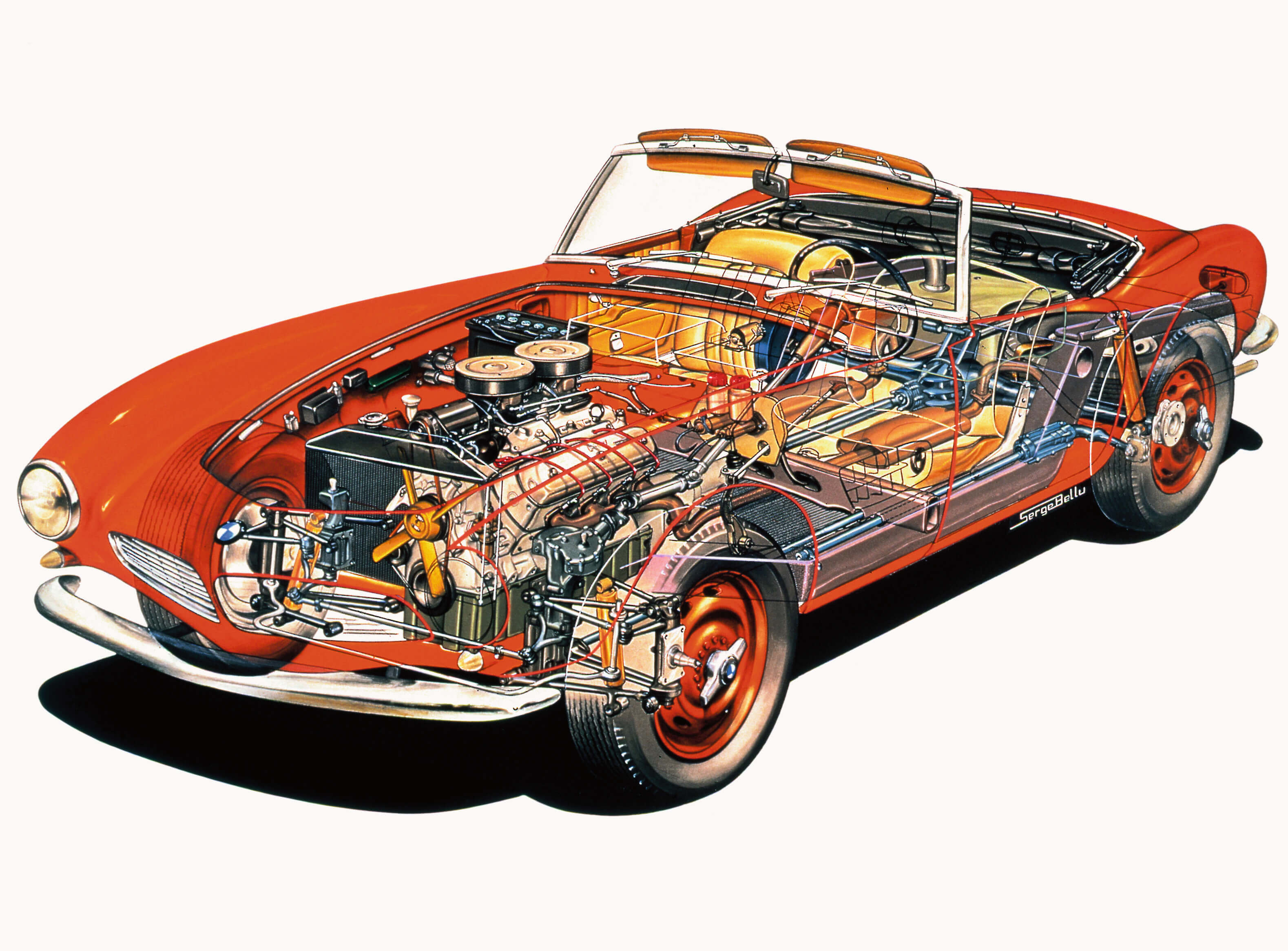

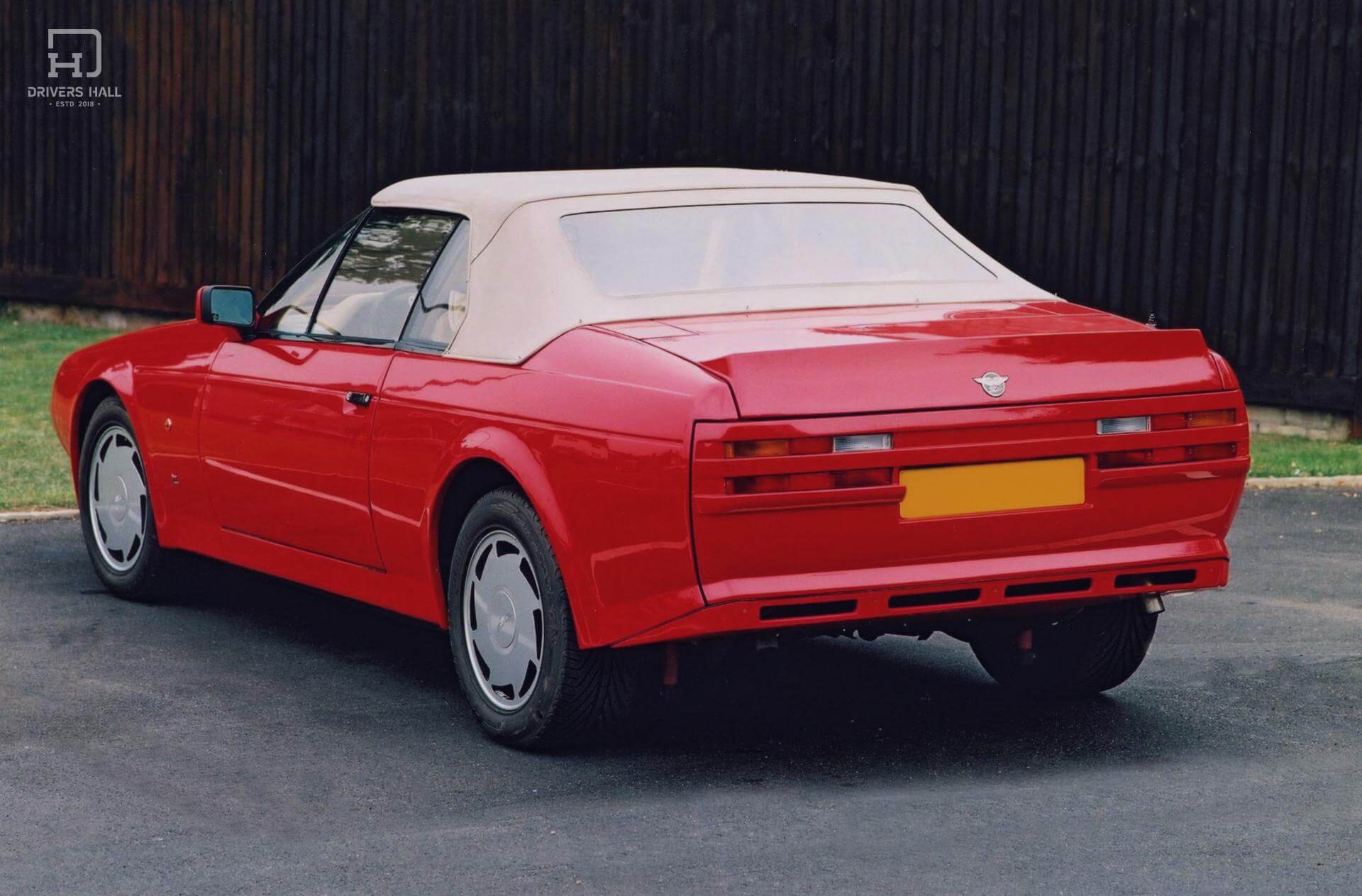

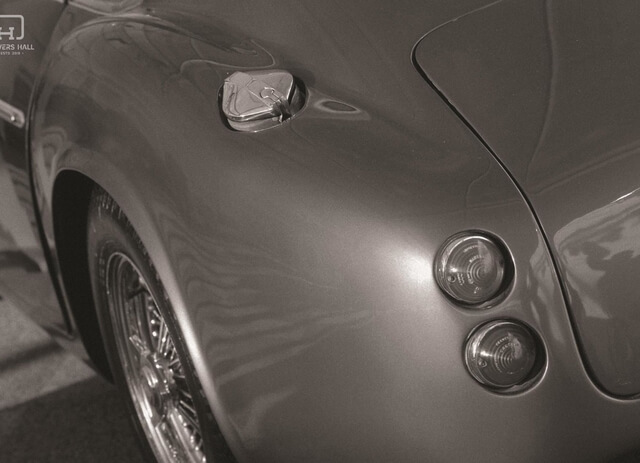

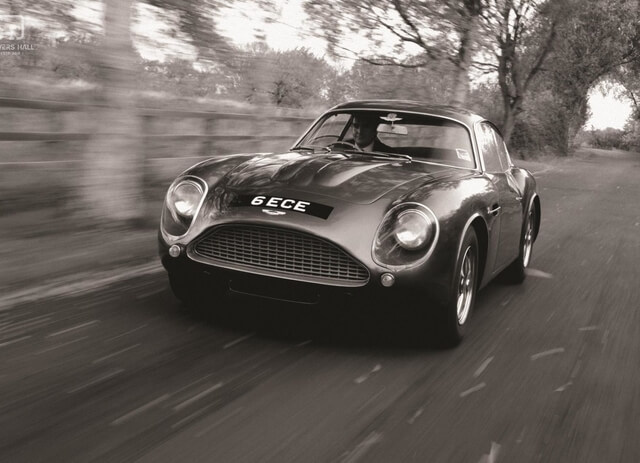

Max Hoffman, buoyed by the success he generated with the 300SL Gullwing and the 190SL Mercedes, suggested that BMW take advantage of the new trend for fashionable sports cars and produce a coupe based on the 502. He felt sure that if it cost 5000 dollars or below, he could easily shift thousands in the US. BMW decided to take the plunge, but the 503 coupe proposal, a four-seater using a lot of 502 carryover parts, was deemed by Hoffman not to be radical enough. He did not like what the factory was working on, so he suggested that his friend, Albrecht Graf von Goertz, a disciple of Raymond Loewy, submit his refreshingly different design. His work was approved for production as the 507, and both the 507 and 503 were introduced to the public in the same year 1955, the 507 in New York, and the conservative 503 in Frankfurt. Unfortunately for the beautiful 507, the expected US sales never materialized, as Hoffman, having learned the car cost twice as much as the initial estimate, more than the 300SL, withdrew his huge order. BMW produced only 252 (or 253, depending on who you ask) 507 roadsters between 1956 and 1959, and even such owners as Elvis Presley (whose car surfaced recently) would not persuade the buyers to part with their money. The car was practically handmade, hence very expensive, its 3.2 liter V8 engine only developed 150 horsepower, and its performance was inferior to that of British cars imported to the US. At the same time the demand for motorcycles, the staple of BMW income, tumbled, and the 500-series of sedans were no longer selling in numbers which would guarantee profit. 1959 was a year of huge losses, and of despair.

Today the BMW 507 is no longer associated with the worst year in the company’s post war history, and most people have no idea what BMW did before the X5 anyway. They just automatically assume it was always making piles of money on cars that sold like hot cakes. The 507, whose styling elements surfaced on the Z3 and the Z8, is now a fantastic investment, with cars reaching well over 1 million dollars at auctions, and recently exceeding 2 million. If you have one in your garage, it can only grow in value. If you don’t, it’s unlikely you will get a chance to try one, so let’s talk about how it drives. (to be continued)