There are few more legendary racing sedans than BMW’s Batmobiles, the bewinged, wide-hipped BMW E9 derivatives which wreaked havoc on race circuits around the world. They won the European Touring Car Championship in 1973 and took a famous class win at Le Mans in the same year, won races in the American IMSA championship in 1975, and did very well in other types of touring car racing all over the world. I once had a little Majorette diecast model of a Batmobile when I was a child, and remember it very fondly. It had purpose and strength visible in its brutal looks, and made other cars of the era look positively effeminate.

And now I am standing next to one, and I am scared. Not of the car, it’s a car, therefore subject to the same laws of physics which I am quite familiar with. Of Dieter Quester, the Austrian driver, a true hero, who has come to Goodwood to drive this car, because I am taking it away from him. Not for long, but he looks at me with a stern unsmiling face, his deeply chiseled features lending credence to the image he projects, perhaps unwillingly. Michael, the BMW Classic mechanic with a Bavarian sense of humor, tells me that over-revving the engine results in the driver forced to buy expensive hamburgers for the technical crew.

I make a mental note, but am sure I’ll forget: the run up the Goodwood hill is so short and so packed with sensations and reactions that my brain will be suffering from overload anyway. The mechanic helps me adjust the seat, and teaches me how to restart the engine,telling me also which dials to watch more closely. The engine is practically brand new, and the car is pristine. Quester drives VIP guests in it at DTM races, probably scaring them to death in the process.

This car is a replica of the car in which Dieter Quester, paired with Toine Hezemans, won their class at the Le Mans 24 hour race, and did so in style. They actually ended up in 11th place overall, in a BMW coupe similar to a road car! The seats and the belts are modern, that’s good, and the gearbox is my BMW favorite, the dogleg Sportgetriebe. I have a lot of experience driving a civilian 3.0 CSL, but the race car in warpaint looks much more purposeful. I am not really apprehensive, as the visibility out of the cockpit is good, the controls fall nicely to hand, and I am not going to try to go fast. Well… at least that’s what I tell the BMW crew.

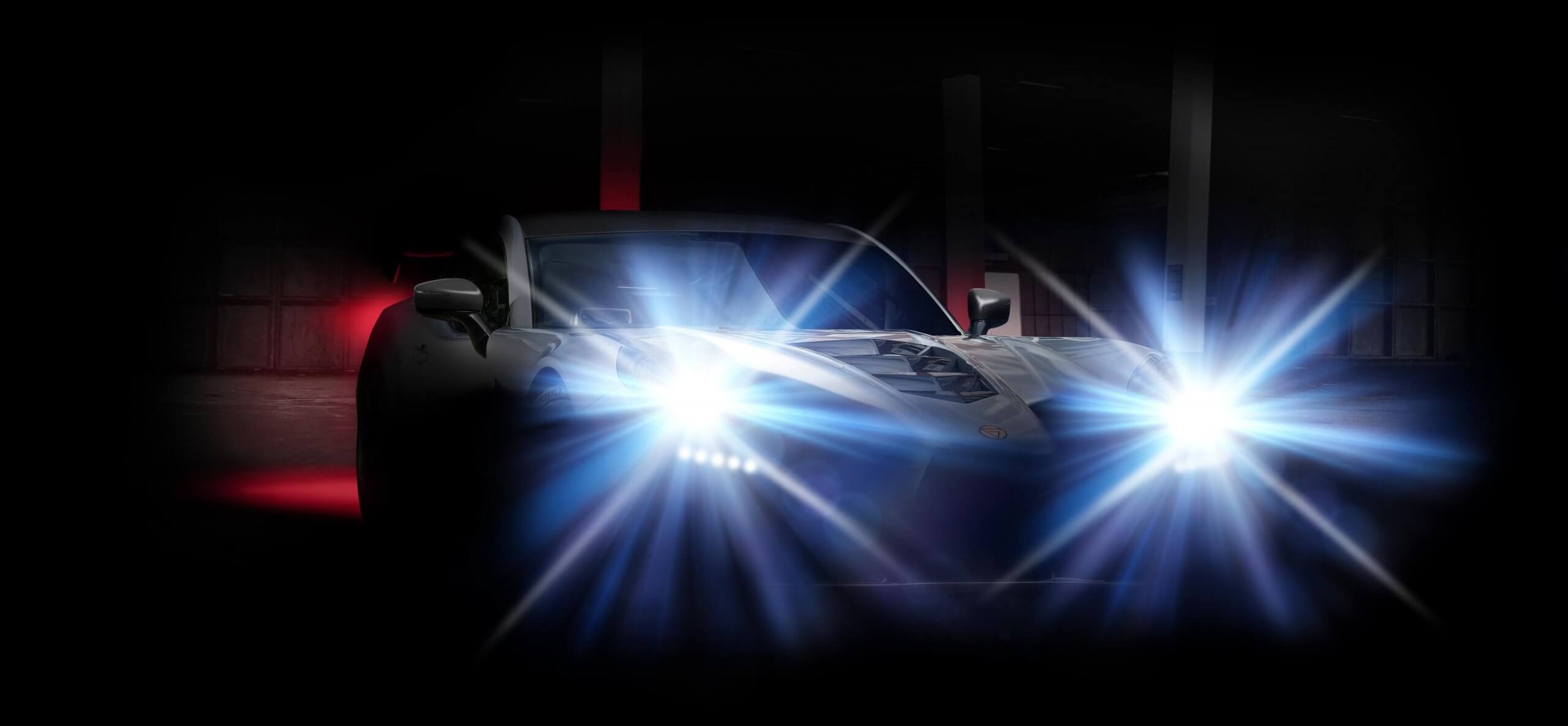

I manage to get the Batmobile out of its tent in the paddock without stalling, drive over to the assembly area without running any spectators over, and finally am directed to a parking space behind the brand new M8 GTE race car. Funnily enough, especially in this livery, the DNA link between the two cars is unmistakable. I attempt to get out of the car gracefully, and fail, but nobody is looking. All the eyes are directed at my buddy, Mike Skinner, called “The Gunslinger” and his hellishly rapid NASCAR Truck.

At Goodwood, when you are driving an unfamiliar car, there is no opportunity to practice, to learn the behavior of the machine, to judge the grip. A short run to the start, turning the car around, a longish wait, and off you go, watched by 70,000 people and millions more on the web and on TV. No pressure at all. I have been driving here since 2010, and I can say I know the route pretty well by now, but even with this kind of familiarity it can be tricky, with slippery dust being blown over it from the vast, dried up lawns.

My launch is OK, but could be better, with the rain tires hooking up in a manner far from a smoothness I want to achieve. The car feels great, only the driver is cautious, because he remembers the look the Austrian gave him earlier. I whizz past Goodwood House, set the car up gently for Molecomb Corner, and continue next to the flint wall and through the last two turns as cleanly as I can. The run over, I park behind the supermodern M8 again, close to the incredibly fast Pikes Peak Volkswagen. Its driver, Romain Dumas,comes over to talk cars, and then runs away toward the rally stage. “i really prefer rallies,” he says with a slight shrug. Yeah, I know, he is helping Porsche develop its Cayman rally car.

And I trundle slowly down the hill afterwards, happy not to give Dieter any cause for concern. He acknowledges my greeting with a curt nod and gets ready for the next run. I look back at the car over my shoulder. What a well-mannered beast. I need to try to drive it again. Unfinished business…