911 Targa (1966-1973)

Many manufacturers were worried, and with good reason, that the American NHTSA would ban the sale of true soft-top convertibles with no rollover protection in the US market; the market where most of the car companies were raking in the biggest profits on this type of vehicle. Thus the British Triumph brand created the Stag with its integrated rollover hoop, and Porsche, for whom US sales meant the difference between survival and a quick demise, decided to drop the traditional convertible altogether, and to build a new bodystyle, which they christened the Targa (after the Targa Florio race, won multiple times by Porsche).

The car had a rollover hoop of 20 centimeters in width and, initially, a foldable soft plastic rear window, later replaced by a glass window. At present it is one of the most collectible Porsche cars ever made, in high demand and thus also a source of income for unscrupulous fraudsters. That’s why it is prudent to peruse our DRIVERSHALL Buyers’ Guide before you make a purchase decision. The car drives virtually the same as the Coupe version of the early 911, and retains most of its practicality.

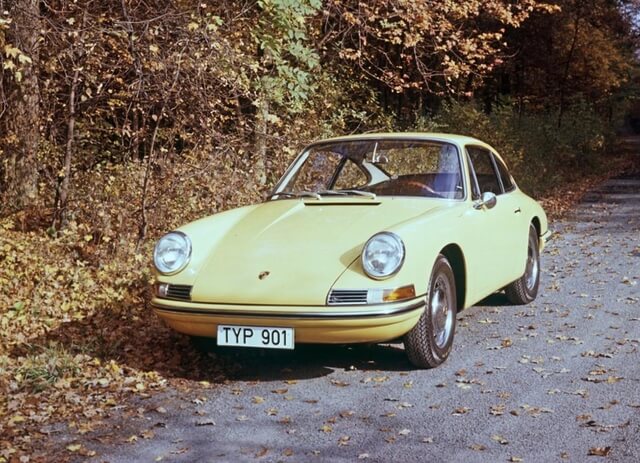

912 (1965-1969, 1976)

In 1965 Porsche was still producing the 356 and a large gap appeared in its lineup between the ageing 4-cylinder car and the 6-cylinder 911, therefore it was decided to create, very quickly, a lower-powered, lighter version of the 911. It was equipped with the 1.6 liter engine from the 1600 SC, and cost as much as the corresponding 356 model. It was named the 912. In 1968 the model received an upgrade, with longer semi-trailing arms resulting in a 57 mm longer wheelbase, somewhat taming the car’s oversteer tendency. In 1969 the Porsche 912 was replaced by the 914. The 912 was produced in the same three body types as the normal 911, that is as a coupe (28 201 units), as a Targa with a glass rear window (2544 cars) and, the most rare of them all, the Soft-Window Targa, with only 967 units built.

The car sounded more like a VW Beetle, and was not a resounding success in period (except in the US), but pundits believed that on tight road courses it actually handled better than the contemporary 911 due to a different weight balance. This made it quite popular in professional motorsport, where, like the more powerful 911, it was extensively rallied (a factory rally kit was available, with anti-roll bars, special brake pads and a footrest to the left of the clutch pedal. Most people today, even 911 aficionados, are unaware of this, but in 1967 the Polish privateer driver Sobieslaw Zasada won the European Rally Championship for production touring cars in a Porsche 912, gathering more points throughout the season than the factory 911S of Vic Elford and David Stone, which had won the Monte Carlo rally! The 912 was strong, reliable and, in the right hands, fast.

In 1976 a partial and temporary resurrection happened, as the 912E was again briefly produced (2099 units) for the US market, using the engine of the 914 (or the VW411, with 90 hp and L-Jetronic injection) in a G-series body. It is the expert’s choice as a great driver’s car, but remains difficult to source.

For decades the 912 was neglected by collectors who despised its “cheap” engine sound, and still a few years ago it was possible to find one in Germany, in decent shape, for around 20,000 euros. That is no longer the case, as the car, especially the rare Targa iterations, has become very popular. It is much less intimidating to drive than the six-cylinder 911, with its more favorable front-rear weight balance, if you don’t mind the lack of outright speed.

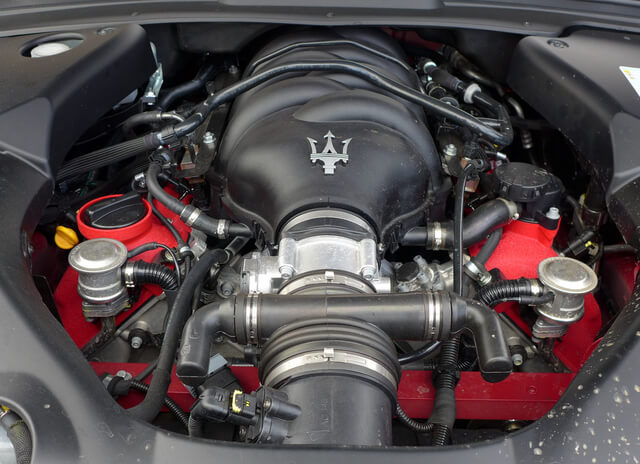

Engine

Porsche 911 Targa

The targa bodystyle was available with all the same engines as the COupe version of the 911 in the same period, therefore the same purchase rules apply. From the start of production, the earliest 911 was equipped with a 2-liter engine developing 130 hp. In 1965 a version of the engine appeared, replacing the maintenance-intensive Solex carburetors with Webers. In 1968 the 911 S appeared with 160 hp, the 911 T with 110 hp became the entry model, and the base car was now called the 911 L. The engine block and the gearbox casing were then made of a magnesium alloy.

In 1969, when Bosch intake tract injection was introduced, the engines gained an extra 10 hp: the 911 E was the base model, and the S was the most powerful one, with the T retaining carburetors until the end of its production.

In 1972 the engine capacity grew to 2.2 liters, and later to 2.4 liters, with the final 911 S developing 190 hp. The most powerful factory engine was the 1973 Carrera RS with light alloy cylinders and 210 hp.

The main source of problems with the early 911 engines is the wear and failure of camshaft drive chains and chain tensioners. Cars with low mileage and irregular servicing are especially prone. Another problem area are the engine head bolts securing the cylinders to the engine block: these can fail catastrophically due to age-related corrosion, and this failure can have nothing to do with the mileage.

It is very expensive to replace a corroded exhaust heat exchanger: this has to be checked by a specialist in early 911s. As the Solex carbs used initially required frequent adjustment, these were often replaced in period with Webers or Zeniths, but original carburetors have a higher collector value. Magnesium engine blocks and gearboxes tend to leak oil. Cars sourced from the US often have the K-Jetronic Bosch fuel injection and are more expensive to fix, even though they seem cheaper to repair at first glance.

Porsche 912

The 4-cylinder engine is normally quite durable, but there are a few caveats. It DOES NOT like long runs at a constant high speed, like on the autobahn! Blue exhaust smoke means worn out valve stems and valve guides. Worn piston rings lead to increased oil consumption, which should not exceed 1.5 liters per 1000 km. US-sourced cars may look promising, but their engines are usually terribly neglected in terms of oil changes and valve clearance adjustment.

But the main problem is a lack of engine originality, as many 912s have had their engines replaced with Type 3 Volkswagen Transporter motors, or even VW Beetle engines with twin carburetors. This needs to be verified thoroughly before purchase!

Gearbox

Porsche 911 Targa

Like most early Porsche 911s, the Targas are equipped with a 4-speed manual gearbox. Much fewer have a 5-speed or the Sportomatic semiautomatic transmission (the latter offered from 1967). The standard gearbox is noisy and requires a firm hand, but is quite durable. As of 1971 the gearbox was replaced with a 915-series unit, with a better shifting action.

Porsche 912

Gearboxes are generally strong, but suffer from damaged synchros and gearshift linkages.

Bodywork

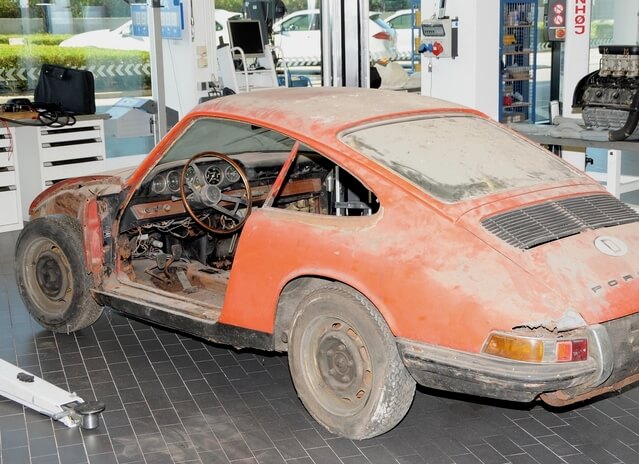

The is just as rust-prone as all the other early 911 variants, and will rust practically everywhere.

Most of these cars rust prodigiously around the headlights, front wheelarches and all the way to the base of the B-pillar. Suspension mounting points also corrode, as do the lower parts of the A-pillars. Another critical area is the special tube to which the rear suspension is attached.

Look for deformations in the inner body structure which can indicate hidden accident repairs! Leaking rubber seals of the rear and side windows mean water ingress into the hat shelf area, which in turn causes corrosionin the rearmost parts of the chassis longerons and the engine bay.

If a car you wish to buy seems to have been restored/repaired/welded, you unconditionally need the help of a seasoned specialist. In the case of cars imported from the USA, often claimed to come from so-called “dry states”, the body repairs performed there are often of horrible quality, just cleverly disguised.

The main difference in this regard between the coupe and the Targa is the fact that corrosion at the base of the rollover hoop can cause distortion to the whole body, as the hoop contributes greatly to the car’s torsional stiffness.

In case of the 912, the majority of the cars in the market come from the USA, where body repairs of horrible quality are the rule rather than the exception. Rust damage to jacking points is very frequent, and unoriginal parts are often used (Porsche originals are expensive). Many 912 Soft Window Targa cars have been converted to the glass rear window. A retrograde conversion is technically possible, but not cheap.

Chassis

The suspension of the early 911 was composed of longitudinal torsion bars and wishbones in the front, and torsion bars plus semi-trailing arms in the rear, and is no different in the Targaand the 912 (except for narrower tires in the latter). The rear arms were lengthened in 1971, resulting in a lengthening of the car’s wheelbase. The car had four disc brakes, later ventilated. At the beginning it has a single-circuit braking system, replaced by a double-ccircuit system in 1968.

It is crucial that the whole suspension system be in perfect shape, correctly maintained and adjusted, with parts replaced on time. The car is quite difficult to drive as it is, and with worn-out suspension it can become impossible to handle for an inexperienced driver. Low mileage is no guarantee of chassis condition.

Look out for rotten shock absorber turrets and rusty suspension mounting points, as they will negate the effect of all other work performed on the suspension.

Interior

The rules for the Targa and the 912 are the same as for any other early 911-based Porsche. The interior needs to be as authentic as possible with no visible damage. Depending on where the car spent most of its life, look for water ingress traces and plastic trim cracked from excessive exposure to sunlight. Replacement parts are available, mostly from Porsche Classic, but are very expensive. Buy the best car you can find. Watch out for worn-out interiors on US-sourced cars, especially 912s.

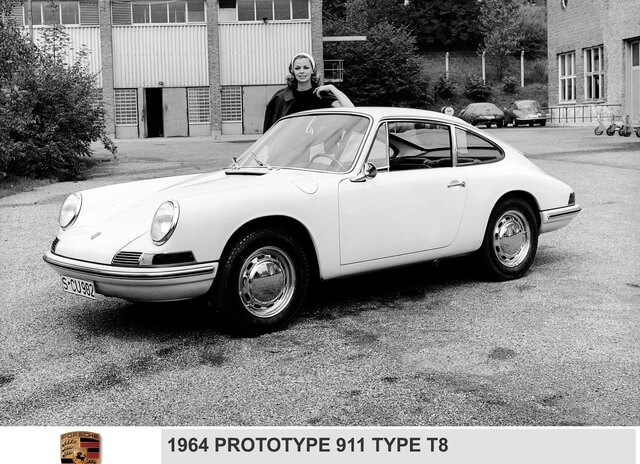

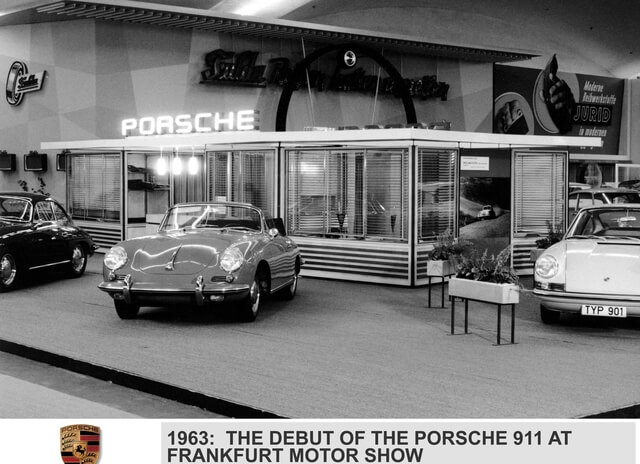

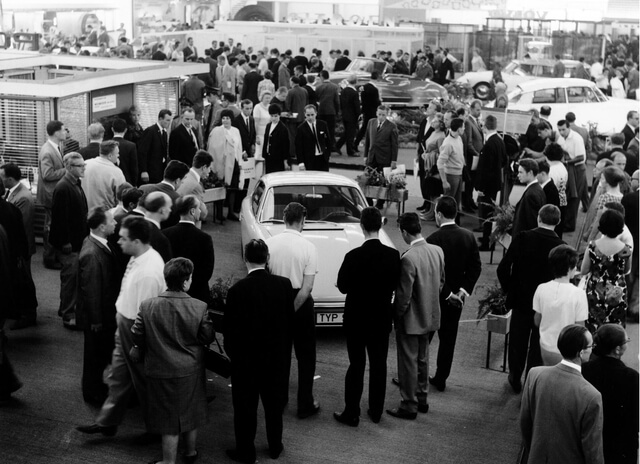

The Story

1965: Porsche 912 launched

1966: Porsche 911 Targa introduced

1967: European Rally Championship won by a Porsche 912

1968: wheelbase increased, double-circuit brakes introduced

1969: Porsche 912 production ends

1973: Porsche 911 Targa production ends

1976: Second-generation Porsche 912E produced for US only

Specifications

Porsche 911 Targa

Power 130 hp

Top speed 205 km/h

0-100 km/h 9.1 s

Porsche 912

Power 90 hp

Top speed 183 km/h

0-100 km/h 13.5 s

The DRIVERSHALL Verdict

The 911 Targa is one of the most desirable classic Porsches, and a delight to drive (if the driver stays within his limits). Because it is so popular and so expensive, many cars are disguised disasters. If a car seems to good to be true, it is. A good-looking car can hide a completely rotten body. Fake restorations often disguise a lack of honest work. A 911 Targa with well-disguised corrosion and component wear will be a veritable money pit, especially as the bodyshell can crack due to the reduced torsional stiffness, especially if the base of the B-pillar is rusty. In the case of the 912, many cars are badly repaired units from the United States, and their recent popularity means that a hasty purchase, without the help of an expert, is a very bad idea indeed. If you bag a good one, it is often more fun than a 911!